Opinion: Getting the Right Exchange Rate Critical to Sustain Tourism Industry

The value of one currency against another is indicated by the foreign exchange rate and it is believed by economic experts that attaining the right exchange rate is a crucial component in achieving economic stability and growth, especially for developing countries. The two most common exchange rate regimes adopted by countries in establishing foreign exchange rates are either a fixed or a pegged exchange rate regime where the local currency is tied to a stronger foreign currency or a flexible or floating exchange rate regime where market forces are allowed to act to determine what the exchange rate should be.

Maldives operated a free floating exchange rate between 1987 and 1994, when the exchange rate of the US dollar to the Rufiyaa ranged between 8.50 and 11.50. In 1994 Maldives moved to a pegged or a fixed exchange rate regime, where the value of Rufiyaa was tied to the US dollar. However, the value of other currencies in terms of Rufiyaa was allowed to fluctuate in line with the changes in exchange rates between those currencies and the US dollar.

In a fixed exchange rate regime, the country which is setting the peg loses a degree of independence over its monetary policy and its ability to control inflation through the setting of interest rates and to freely manage its money supply. It must ensure that the quantity of its own money that is in circulation in its economy remains in balance with the quantity of dollars available to be exchanged at the set rate. This becomes especially problematic in economies which are highly dependent on imports and operate in current account deficits – i.e. the amount of imports is more than what it exports.

As the value of the US dollar strengthened against other major currencies and the Maldives’ economy developed, the government’s and population’s requirement for imported goods rapidly grew above the pace at which the tourism industry could bring in foreign currency. At the same time oil prices increased and the revenue the country was generating through fish exports also tightened. This resulted in the exchange rate being overvalued against US dollar, which lead the government to devalue the Rufiyaa in 2001, where buying rates and selling rates were fixed at MVR 12.75 and MVR 12.85 respectively.

When the global financial crisis hit in 2007-2008, the Maldives again faced a shortage of US dollar inflows and the fixed exchange rate became considerably overvalued. This led the Maldives Monetary Authority (MMA) to revise the exchange rate regime in 2011, allowing a horizontal band of 20% fluctuation on either side of the fixed rate of MVR 12.85 per US dollar. The official announcement was that the country moved to a floating band in the range 10.28 to 15.42 per US dollar, but in practice the official rate has been steady at 15.42 since the change and devaluation, while at the same time a parallel (black) market has developed with higher exchange rates. The mismatch and the parallel market premium remained relatively stable during 2017-2019 when tourism was doing relatively well and there was a lot of infrastructure investment in the country, with the rate at about MVR 15.85 per dollar.

Since the second half of 2020, the premium has increased significantly, when the country went into deep recession due to the COVID-19 pandemic and faced a massive reduction in foreign exchange inflows. At present, there appears to be a significant mismatch in the foreign exchange market, and the parallel market rate is at about 16-20% above the official upper band of 15.42.

Mismatch in the foreign exchange market and the current account deficit

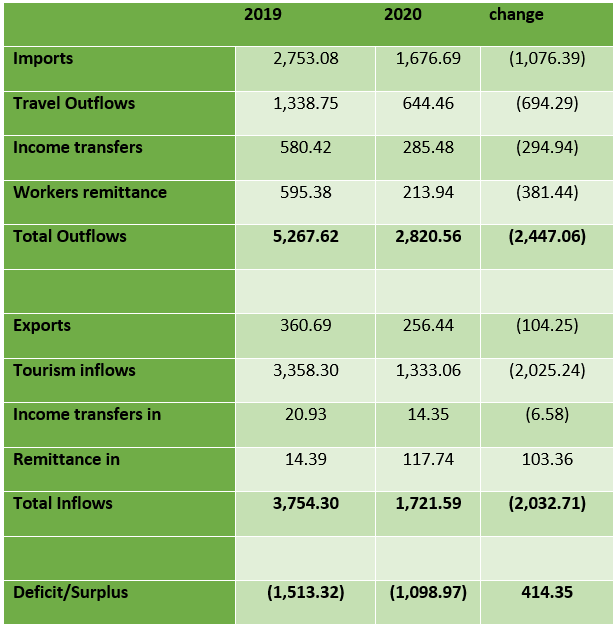

As the Maldives economy is over-reliant on the tourism industry, almost 90% of foreign currency inflows are contributed by the sector. In fact, as per 2019 government figures, tourism receipt inflows are estimated at USD 3.4 billion. Inflows from fish exports and other merchandise exports contributed USD 360 million in 2019. The total inflows recorded in the current account of the Maldives is estimated to be at USD 3.8 billion during the year. However, the total outflows during the same year stands at USD 5.3 billion, resulting in a USD 1.5 billion deficit in the current account. In other words, a net outflow of USD 1.5 billion. The current account is a key indicator of economic strength, which is the balance of trade – export of goods and services minus imports, plus net investment income from abroad and net transfers. A deficit current account balance simply means that the total value of imports is higher than the total value of exports which will result in net outflow of money from the country.

The Maldives spent almost 73% of our foreign currency earnings on Imports of goods (USD 2.8 billion) in 2019. Another 36% of receipts (USD 1.3 billion) flowed out as travel and transportation expenditure by Maldivian residents. Additionally, 16% of the receipts (USD 595 million) flow out as workers’ remittances for the country’s large expatriate population. In total, 140% of the total foreign exchange inflows left the country in 2019, meaning for every USD 100 the country brought in, we have spent USD 140 during that year.

If so, how have we funded the over one-billion-dollar imbalance per year over the past 5 years? It had to be financed by a combination of Government and private sector borrowings, foreign grants, and foreign direct investments. Considering the total direct Government borrowings during the past five years (as per the published debt statistics), we are looking at over USD 4 billion financed by the private sector in the form of borrowings and equity investments.

When a significant component of the current account imbalance is financed through external borrowings from the private sector, such borrowings will incur debt repayments every year. This is reflected in the ‘Income transfers’ under the Outflows in the Table below.

How has it changed due the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic recession?

Maldives closed its borders on March 2020 and as a result all tourist facilities were shut down. This was soon after record-breaking tourist arrivals in 2019 with almost 1.7 million tourists, and it was the first time in the history of the country that the country experienced a total shut down of the tourism industry. The borders reopened 3 months later on the 15th of July 2020 but with only a limited number of resorts opening and very low tourist numbers. Tourist numbers started to to pick up significantly only in December 2020.

With all the resorts out of operation for more than three months, and limited occupancies for the rest of the year, the total tourism receipts decreased by US$2 billion and total imports of the country in 2020 declined by more than USD 1 billion, saving the country about USD 90 million per month. Similarly, with international borders closed, and Maldivians’ travel restricted, outflows from outbound travel also declined by USD 694 million in 2020. Additionally, the total of income transfers and workers’ remittances combined declined by USD 676 million as banks instated interest and debt repayment moratoriums and foreign workers were sent home or put on reduced pay. As a result, the total outflows during the year recorded a reduction of USD 2.4 billion compared to 2019, and the country reduced its net outflows by USD 414 million, as the fall in inflows was at almost USD 2 billion.

What has caused the misalignment?

What has created the imbalance in the exchange rate? In addition to the country having a current account deficit exceeding 20% of GDP over the past 5 years, the present imbalance in the foreign exchange market is also due to the extremely difficult economic conditions. The government has had to monetize over 45% of its expenditure by borrowing from the central bank or by printing money. The Maldives’ Ministry of Finance had borrowed about MVR 4 billion from the Maldives Monetory Authority by July 2020 (by January 2021, part of it has been repaid back) and as at January 2021, the net borrowings over the past 12 months remains at MVR 2.7 billion (which is a 45% increase in money supply in the form of newly printed money).

Financing Government expenditure by printing money is the worst macroeconomic management prescription, and one that will definitely bring about an imbalance in the foreign exchange market. Government debt monetization specifically in weaker and less-developed economies will lead to excessive inflation and weakening of the local currency.

With such a fundamental imbalance, introducing administrative measures that make it harder to conduct business in the country and new regulations on capital controls would only make things worse by losing investor confidence, central bank credibility and leading to further speculation.

There is much debate on whether the shortage of foreign currency is due to the secret hoarding of dollars by tourism investors and whether de-dollarising measures can be used to address this problem. The facts are that businesses in Maldives are subject to a very efficient tax regime administered by MIRA and it is impossible to hide income and profits through transfer pricing. All tourism income is received into local banks which are well regulated by the MMA and the whole system is highly transparent. The industry pays its taxes, suppliers and staff (local and expatriate) in US dollars, which allows a large portion of the foreign exchange to enter the local economy. The balance goes to creditors and investors – it is this part that makes the Maldives an attractive opportunity for foreign investors and any actions that harm this will be detrimental to the prospects of the industry that brings in 90% of foreign exchange to the country.

There is a fundamental imbalance between the inflows and outflows of foreign exchange in the country due to the excess in Ruffiya supply circulating in the economy. De-dollarizing the economy will not increase foreign currency inflows, instead it will hand control of the entire foreign currency supply to the government which will still not be able to match supply and demand but be subject to allocating foreign exchange to its obligations based on political motives. If the fixed exchange rate is maintained, there will continue to be a shortage of foreign currency with the only difference being that it will become harder for the tourim industry to gain access to the dollars it needs to function – this in turn will have very significant consequenses for the entire economy which is so highly dependant on it.

It will be practically difficult to bring about de-dollarization measures at a time when there is huge imbalance in the foreign exchange market, and when business confidence is at an all time low. Success stories of other economies which de-dollarized had high growth rate, low to moderate inflation, strong monetory and fiscal policies. Any de-dollalization measures can only be sucessfully applied gradually with proper sequencing of macroeconomic policies. Who will want to convert their foreign currency savings with the knowledge that the value of Maldivian Rufiyaa is falling by the day?

The bottom line is, when the macro-economic fundamentals are mis-aligned, there will always be imbalance in the foreign exchange market. That has been the case in the Maldives. Without establishing monetary credibility and a sound fiscal policy and regaining confidence in the domestic currency, there will be no easy way to move out of this crisis. Administrative changes, or capital controls will only make things worse and create more panic and uncertainty. Direct controls on capital outflows and direct instruments of monetary policy (with limited foreign currency reserve) are never an option to stabilize the exchange rate in small open economies and will irreversibly damage the one industry that the country relies on to survive.