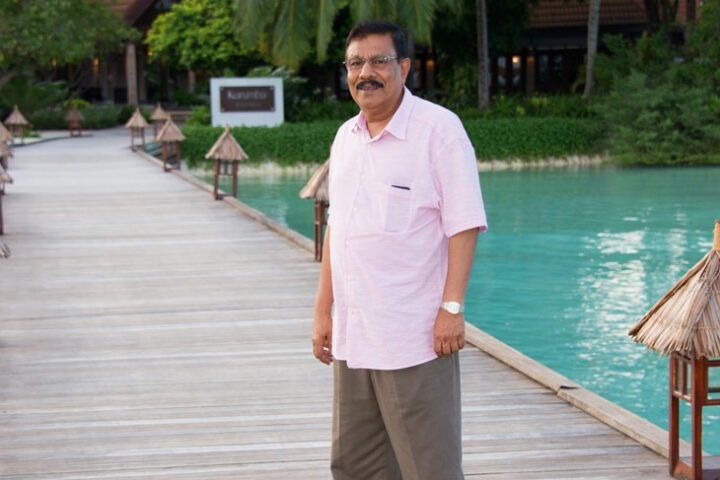

Exclusive: M.U. Maniku – Crafting a Legacy

Sitting in the board room of the Maldives Association of Tourism Industry (MATI), of which he has been the chairman since inception, Mohamed Umar (MU) Maniku begins to give an account of how he found himself involved in tourism. His memory does not seem to be tarnished by the years, and as he speaks, his love for his work and its legacy is apparent, as is a sense of humour.

He was just a young man who, after finishing studies in Pakistan, was serving the Maldivian government when opportunity knocked on his door. “It was really a matter of coincidence,” says Maniku. “There was hardly anything here besides government service when I came back after finishing college in ‘72.”

Even at that time tourism was very big in Asia, Maniku recalled. The Maldives’ neighbour Sri Lanka already had jumbo jets coming chock full of tourists. “It was big in Thailand too,” Maniku says. “Also in Seychelles. There were direct flights [from Europe] to Seychelles. But we had nothing here in the Maldives.”

And tourism prospects seemed rather bleak. A few years prior to Maniku’s arrival, The United Nations had conducted a study – much derided since then – that found tourism to be unfeasible in the country. There was no infrastructure or facilities to support the industry.

The advent of tourism

But it so happened that Maniku, along with his friends Ahmed Naseem and Hussain Afeef (Champa) met a European man by the name of George Corbin who visited the Maldives looking for new destinations. Corbin was into spearfishing, a practice that is now banned in the country. He had taken some rich Italians to Bangra in India on such an excursion and found the Maldives to be very promising.

“When Corbin and his friend came here, we put them up in our own homes,” says Maniku. “Naseem, myself and Hussain Afeef (Champa), took him around town just like we would any foreigner those days. We were just youngsters then. We took him to some nearby islands and they took a lot of photos.” Corbin, who represented the travel agency Sesto Continente in Milan, told the group that he could get some people down for spearfishing the following February.

“We were very excited,” Maniku beams. “We were young and wanted to do all that we could to prepare for this.” But at that time, the Maldives did not have means to communicate to the outside world besides Morse code. So the wait was fraught with anxiety. “He communicated with us through Morse code,” says Maniku. “But the messages would have to go through Colombo from here.”

But the wait was finally over and the Maldives’ first tourists arrived on a chartered Air Ceylon flight to Hulhule’, on 28 February 1972. They were put up in friends’ homes. “We did not know what to serve them,” Maniku laughs. “But they had brought their pasta and things, so it wasn’t much of a problem.” Everyday around four in the morning, Afeef and Maniku used to go to Maagiri, one of the residences of the guests, to prepare breakfast. Then, at about 7 o’ clock, they used to take them on boats to shoot fish, in different reefs and around different islands. They would do this all day and come back in the evening. “That’s the story of the first overnight group of tourists who came here,” says Maniku. “It’s history that nobody can dispute.”

Kurumba: The first resort island and the end of spearfishing

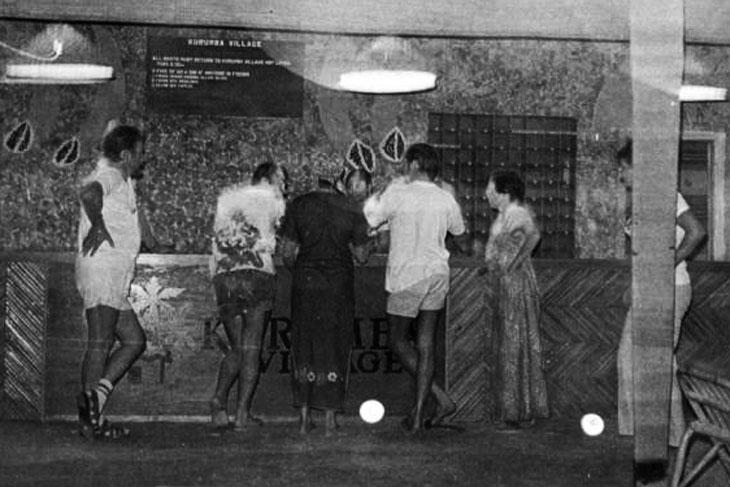

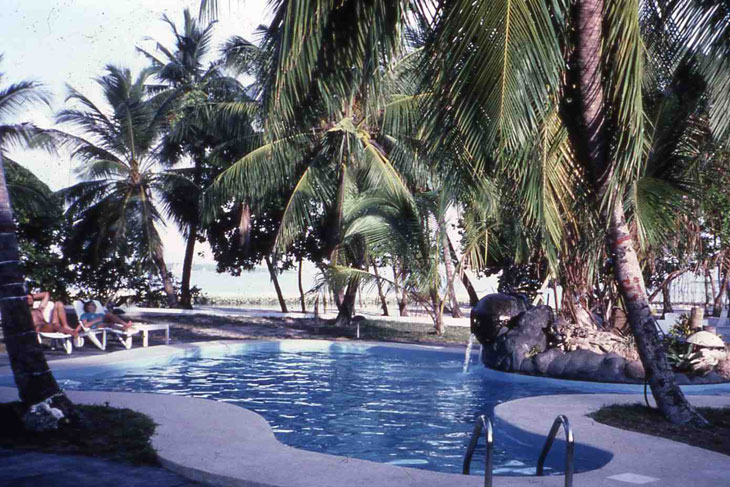

Then, because Maniku and his friends were convinced that Corbin will deliver guests, they started building what is now Kurumba, pooling in resources. Initially they constructed thirty rooms with cut coral walls and coconut thatched roofs. There was tarpaulin on the floor although the bathrooms were tiled. “It was very simply done,” says Maniku. “We were very lucky in a way because we took on board the suggestions of tourists when we built the place.”

It took about eight months to complete; right on time for the next batch of tourists who were to get the first ‘island resort’ experience. Maniku and his friends procured a generator and received supplies for the resort from Sri Lanka. “I myself was the cook in the kitchen,” he recalls. “I worked for many years in the bar too, every day. We had to do things ourselves, we didn’t think to depend on anyone else. We had the energy somehow, and the drive to do this.” The island began to receive regular well-to-do visitors through Corbin. And its name was already being established abroad, especially in Italy by those who had stayed; they gushed about the island, the new destination in Asia, a veritable Paradiso.

Spearfishing however was a common pastime among tourists even then. “But we met some person, I think from the World Tourism Organisation,” says Maniku. “And he said: ‘My goodness you’d better stop this harpooning business, it’ll kill all the fish life.’ And we ourselves had seen this, because after a group of guests shot fish in Funadhoo [island] area, there was practically no fish for five months. So we stopped it.” Subsequently, legislation was passed to ban the practice throughout the country.

Growth

With word spreading about the Maldives in Europe, bigger tour operators began to take an interest. “The word that Italians were coming here spread to Sri Lanka,” Maniku says. “It is a major hub of European tour operators.” Their scouts came to the Maldives on small aircraft. Tour operators soon began to sell Maldivian excursions.

“Apart from the Italians, among the first guests to the country were Swedes,” Maniku explains. “They started coming through the Swedish operator Vingressor.” This was followed by Kuoni and others.

With new flights coming in, the Maldives began to grow as a destination. But it was a tough time. There were great difficulties in getting supplies. The airport was not built to cater to large aircraft so flights arrived in the Maldives from Sri Lanka; there was no direct link to the European market. This meant that Sri Lanka made money off tourists wishing to spend time in the Maldives, through packaged stays. “But we built the airport eventually,” says Maniku. “And the day that the Maldives truly became an independent destination was when [the carrier] Condor landed here. And we were instrumental in bringing the flight.”

Universal’s Strategy: Luxury tourism

Universal Enterprises, of which MU Maniku is chairman, believed that it was important to elevate the Maldives from its then status as a low-end destination. “We realised that the Maldives as a product had all the ingredients to be an excellent one,” Maniku remarks. “Why can’t we create something in the Maldives that was on par with the top destinations abroad?” With that train of thought Maniku and his associates scoured tourist hotspots like Bali and others. He was convinced that it could happen here in the Maldives.

To this end, they started rebuilding Kurumba, under the guidance of a German designer. But at the time, Maniku notes, they received negative feedback from mass tourism operators who were sceptical as to whether the new product could be sold. But Maniku went ahead without their blessing. “We added all the ingredients to make a modern resort,” Maniku says. “We also made restaurants on the island because we felt guests should have more variety during their stay.” It turned out to be a bold and fruitful endeavour. Also it set an example for other resorts to go by.

Breaking the shell; beyond luxury, partnership with international brands

Despite the progresses that resorts made in the country, there was only so much that they could do by themselves. “We as a local brand came up against a barrier that we couldn’t break through,” says Maniku. “We believed that we needed the expertise, the marketing strength, the knowhow of reputed international brands.”

In the mid-2000s Maniku became involved with Starwood Hotels, who were seeking an island in the Maldives. They began to develop what is now W. “We were very keen on it, it was a new beginning for us,” Maniku says. “This project was driven from Singapore, with a Singaporean architectural firm’s involvement.” The design incorporated uniquely Maldivian features with modernity. “It had a huge ‘wow’ factor,” Maniku laughs. There was an equity partnership between the two companies and it was one of the first American investments in the country, Maniku is proud to emphasise. “It was the first W resort in the world,” he exclaims. “It became such a big hit worldwide.”

It was an eye-opening experience for Maniku and his company. At the same time it made the Maldives into a top end destination.

Universal also has stakes in Per Aquum, which runs Huvafenfushi and Niyaama in the Maldives and others in Zanzibar and Dubai.

Present Concerns

Now in his late sixties Maniku is still very much engrossed in tourism. He is building two properties in Raa Atoll with his family; something that keeps him occupied. Also, he is still MATI’s chairman, a position he takes very seriously. He believes MATI’s overarching purpose is to protect the tourism industry, and he is determined to do so. And looking back, he has blazed a trail for others to follow. But he does not seem to be in need of rest. “The fire is still in the belly,” he says. “It’s still going strong.”